New Yorker Fiction Reviews: "The Largesse of the Sea Maiden" by Denis Johnson

Yet again, I bring you one of the living legends of literary fiction: Denis Johnson. If you've never read his short story collection, Jesus' Son, do so immediately after you read this blog post. Seriously, it's that good. Johnson has won or been nominated for just about every literary prize you can possibly win, the Pulitizer having eluded him twice (though he was a finalist).

Yet again, I bring you one of the living legends of literary fiction: Denis Johnson. If you've never read his short story collection, Jesus' Son, do so immediately after you read this blog post. Seriously, it's that good. Johnson has won or been nominated for just about every literary prize you can possibly win, the Pulitizer having eluded him twice (though he was a finalist).Having said that, I'm sad and embarrassed to say I've never read anything of his but Jesus' Son and the short story in question here. Although I did own a copy of Tree of Smoke for about five years and even opened it a couple of times. That's probably his most critically-acclaimed opus, while Jesus' Son is what he's best known for...there is a significant difference, mind you.

Suffice it to say, Johnson is a heavy-hitter for the Contemporary Literature All-Stars and he's delivered a grand-slam of a story with "The Largesse of the Sea Maiden." Apparently the story took him eight years to write, which is not surprising because the story has an epic feel to it, covering decades of the main character's life. Johnson accomplishes this by linking seemingly mundane details and scattered memories of the main character's life into a broader meditation on mortality. And, when it comes to themes in literature, it doesn't get more universal than mortality.

The spectre of death seems to be everywhere around the main character, Whit, as he traverses middle age. He gets a call from one of his ex-wives who is on her death-bed and trying to forgive him of his past indiscretions; one of his dear commits suicide unexpectedly; he bumps into the son of his former colleague, and mistakenly thinks it is his former colleague, only to find out that his former colleague has long-since passed away. All of these brushes with death serve to re-enforce the fact that time is passing.

Whit is not scared, however, has advanced past mid-life crisis territory, in both years and wisdom. On the surface, it might seem as though he has resigned himself to the banality of life and his own inevitable regression toward the mean. On the contrary, I think Whit is able to look back at his life with a clear set of eyes and recognize that he's satisfied with the experiences he's had and is grateful for whatever else life might bring him. This, I believe, is evidenced in the way he allows himself to indulge in occasional flights of whimsy, walking around the neighborhood at night in his bathrobe and slippers:

"I wonder if you're like me, if you collect and squirrel away in your soul certain odd moments when the Mystery winks at you, when you walk in your bathrobe and tasselled loafers..."

I see this as a profound and yet very easily overlooked meditation on aging. Here, Whit is not only breaking the literary fourth-wall, but he's addressing the fact that his dreams have shrunk down appropriately to fit his life, as they do for almost everyone who is not either wildly self-actualized (read: rich or famous) or insane. In simpler terms: he has learned how to ask less of life, so that he is always satisfied with what he gets.

His moments of delight in the "Mystery" of life have become so rare and fleeting that he now has to "squirrel them away" because he understands how precious they are. I don't necessarily think one has to be "old" to understand this, but one does have to have a profound appreciation for the brevity and delicateness of life, a type of understanding that is vastly more common in adults than adolescents.

It's taken me almost an hour to home in properly on just one aspect of this story. If I tried for another week I don't think I could completely do justice to my feelings and thoughts on this piece of fiction. I will have to re-read it and think about it more. But, suffice it to say: it's highly worth the 45 minutes or so of your time.

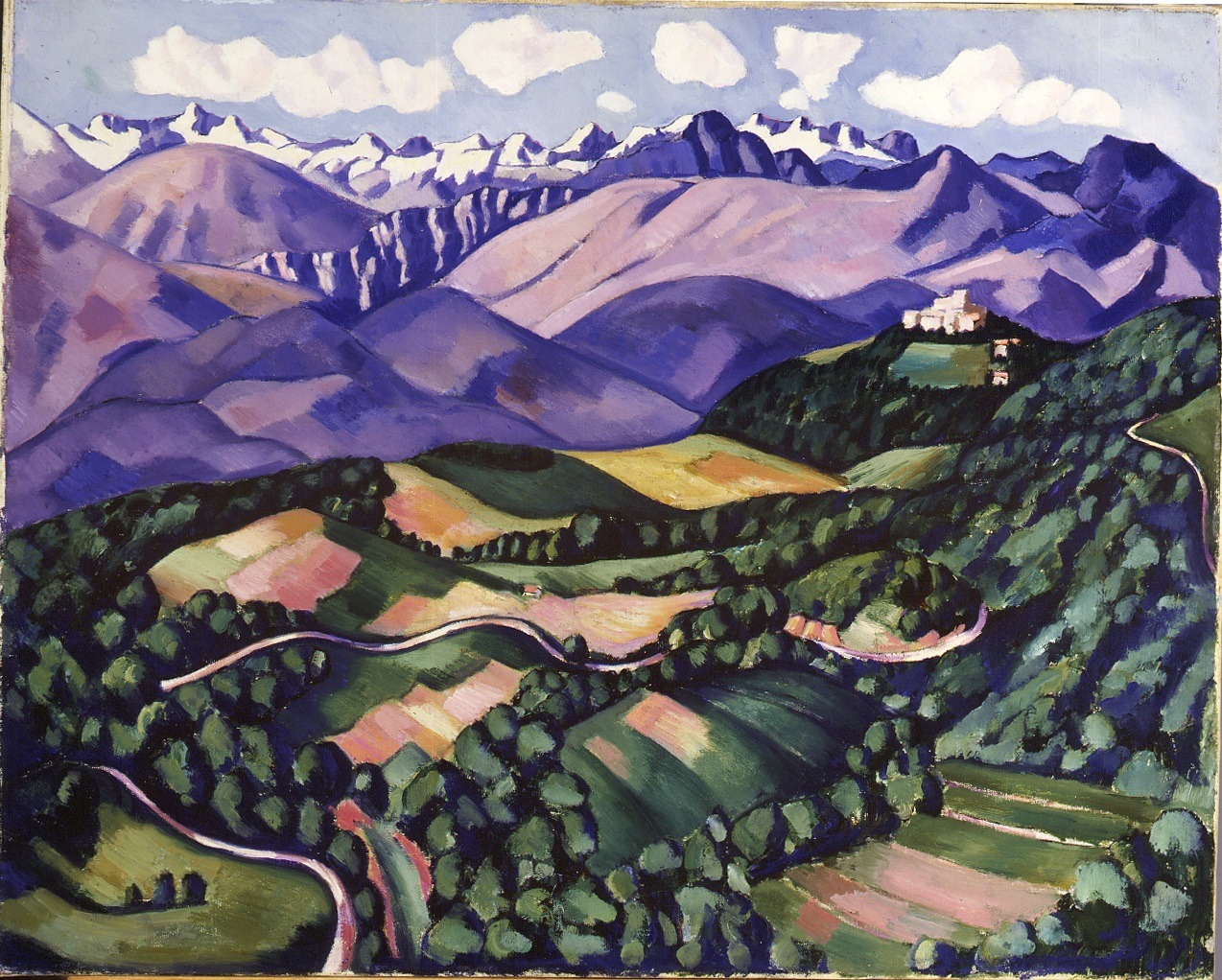

It's taken me almost an hour to home in properly on just one aspect of this story. If I tried for another week I don't think I could completely do justice to my feelings and thoughts on this piece of fiction. I will have to re-read it and think about it more. But, suffice it to say: it's highly worth the 45 minutes or so of your time.On the Intertextuality Front: In the opening "scene" of the story, Whit watches his friend burn an original landscape painting by Marsden Hartley. Upon about 90 seconds of internet research, I cannot find any connection between Marsden Hartley and "sea maidens" (and anyway, Johnson has explained the "sea maidnen" thing in the story and it's not that interesting); however, Hartley seems like a really interesting modernist painter whose work is worth further investigation [painting shown above left].

Comments